Introduction

It was bright pink that morning—bloody urine. There are moments when you realize you have to go to the emergency room. In films, those moments are often depicted as chaotic. But that Monday morning, I walked slowly to my wife in the other room and told her we should go to the ER. We walked steadily, quietly to the hospital. I was breathing large deep breaths to prep myself for a visit that I knew would last at least four or five hours. I had something like a hypertensive attack, as well as a urinary tract infection. It’s also likely that a cyst burst in my kidneys. The most memorable part of that day was a sign outside of the hospital. It was meant to indicate where the new emergency room was located. The sign was, in fact, not pointed toward the new emergency wing, but instead pointed directly up to the sky. This writing is about absurdity. It’s about moments when you are bleeding internally and are told the room you are looking for is in the sky.

Sacrifices were made

Doctors hold a power they surely can’t fully understand. Doctors, nurses, CNAs, phlebotomists, technicians create a network, a force, a clergy, a church, a faith that distributes care and judgement. Implicit, explicit is the reality that there is a standard, a beacon, a perfect body, a perfect health one should strive for. And we should do anything to achieve it. Pay any price. Sacrifices will be made. And though all bodies should strive to be this body, you must prove yourself worthy to become this body.

“And if thy right hand offend thee, cut it off, and cast it from thee: for it is profitable for thee that one of thy members should perish, and not that thy whole body should be cast into hell.”Mathew 5:30 KJV

In one of the most infamous stories in public health—and certainly in medical ethics—Seattle Artificial Kidney Center established a committee in 1962 to decide who would receive some of the very first dialysis treatments— very costly treatments. Detailed in 2009 Washington Post article, John Buntin explains:

“…with help from a $100,000 foundation grant, Seattle’s King County Medical Society opened an artificial kidney clinic at Swedish Hospital and established two committees that, together, would decide who received treatment. The first was a panel of kidney specialists that examined potential patients. Anyone older than 45 was excluded; so were teenagers and children; people with hypertension, vascular complications or diabetes; and those who were judged to be emotionally unprepared for the demanding regimen. Patients who passed this first vetting moved on to another panel, which decided their fate. It soon gained a nickname — the “God committee.”

Born of an effort to be fair, the anonymous committee included a pastor, a lawyer, a union leader, a homemaker, two doctors and a businessman and based its selection on applicants’ “social worth.” Of the first 17 patients it saw, 10 were selected for dialysis. The remaining seven died.”

I will need dialysis one day. Thankfully, dialysis has become more available. And I will be able to choose what flavor of medical duopoly I’d like to become indebted to. Though kidney transplant recipients undergo a not-too-dissimilar process of selection, of worthiness. Separating the wheat from the chaff beyond closed doors, a team of experts, a panel.

Obvious, oblivious

After being man-handled by the blood pressure monitor (it has quite a grip), I found myself dangling my legs on the foam examination table/bed/bench, getting grilled by the intake nurse about my medical history. I had been dreading this particular visit. I had seen one other nephrologist before this, and I knew where this visit would go. My current kidney condition has one treatment and no cure, so the doctor really didn’t have much to do. Going to the doctor can often feel like being told the obvious is not obvious.

“Have you heard of Jynarque?” (Jynarque being the only medication for polycystic kidney disease.)

“Yeah,” I said, “I’ve been told about it before.”

“I recommend you start this medication” the doctor said. “I’m worried about price, how much does this medication cost?” I sheepishly asked.

“You have insurance?” the doctor asked, or maybe retorted.

Sometimes going to the doctor is being told the obvious is ridiculous. I had insurance—but I don’t think that was the question. That question, or rather question as accusation as statement, became a mood, a tone, a precedent. “You have insurance?” He wasn’t asking if I had insurance; rather he was asking, “don’t you trust me?”

What became clear was that asking questions, questions that questioned if the recommendations given were even possible due to my student income, was not welcome. It is true that most insurance covers the cost of Jynarque. And most people only pay a $10 copay. A fact not made clear to me. Another fact not made clear to me was that the actual cost of said medication, per package, is $17,000. Knowing the difficulty of getting insurance to cover the high cost of my medical care, I had become accustomed to asking what the cost of things were. I didn’t need to explain the precariousness of insurance to this man. It was becoming obvious that he would not answer my question.

Emergency Time

I was curious if the metal detector was for my protection or for theirs. My knee had swollen to the size of a melon, so the guard didn’t force me to walk through the metal detector. My partner was with me, helping me get checked in. The pain in my knee was giving me a bit of a delirium during our midnight emergency room visit. I have forgiven myself for not totally registering when the guard said the wait time was around eight hours. Emergency time is not obvious. The word “emergency” makes one think of urgency. But emergency rooms are where one might experience the most waiting. Hospitals rooms are places of waiting, and their lobbies, waiting rooms.

Waiting and wailing.

Visitors wait before they are seen. Not yet seen, but certainly heard. Some people in pain need to express,— release—pain in the body. In cold white rooms—quiet like libraries—people politely gnash and wail, strain and stress. During that particular stay, a television positioned at an angle (just beyond comfortability), was playing The Joker. People were watching simply to pass the time. Certainly the murders on screen set a specific tone.

For all the waiting that happens, there is little resting. The chairs are all hard and cold. People are trying to sleep, but with shallow breaths, because at any moment they could be called back, back to be seen. If you are asleep, you can’t hear when the nurse calls you back. Seen and heard.

People are hungry, and mercifully, there are vending machines to provide starches to keep one’s energy up. Leaving the ER to get food might forfeit your place in the queue. The nurse calls patient’s names three or four times. If they don’t see you, you don’t get seen. You could go home, and come back, but you might loose your spot, and not get spotted.

“Julian Harper?”

A statement, question, and command. I’m being seen. Being called back. My wife and I are led to a new room, a patient room. Waiting, but by ourselves. Then comes the questions.

“Why are you here?”

“Why is your blood pressure so high?”

“How long has your knee hurt?”

These questions are better than others I’ve gotten. “Are you sure?” is a common refrain. Questions are about confirmation, confirming suspicions. Questions are given to reveal an answer that the nurses, the doctors, think they already know. That you fucked up. That’s why you are here. Here with us, with your gout. With your knee.

“What did you eat?

“Do you drink?”

“Did you eat fish or meat?”

They think they know the answer. But the answer is no. The nurse took a sample. Using a needle the length of a pencil, the nurse stuck my knee as one would stick a balloon—just so, to make sure it doesn’t pop. They drained the knee. And from me swirled a cocktail I’m told was full of crystals. They took my gem goo off to the lab to confirm that I had gout. My wife was in the corner, slumped, as both of us were delirious from exhaustion. By that time, we had been up for close to 36 hours. We got some medication and a referral.

“See a rheumatologist, see your primary care doctor.”

A little while later I had another episode, another flair up. This time it was familiar, this time we had a car, this time we knew the signs, this time I had a specialist. I had an appointment. I waited about 30 minutes.

Holding Breath

“15 seconds…and breathe.”

To get a good image, I need to hold my breath. Sometimes it’s an ultrasound. The technician pushes and guides the equipment into my side.

“Am I pressing too hard? This may be cold.”

It’s an intimate position. Some ultrasound techs are quick: quick images, flashes. But most, in my experience, take the time to ask how I am doing. How I’m feeling. They are there to get a good image. A good sense of things. I can hear my heart moving.

“If you can, try to turn on your side…Perfect.”

I can’t recall many times I’ve been told I’m doing a good job in a hospital. Even though I know there isn’t anything specific about me that is spectacular in those moments, it’s nice to hear.

“15 seconds…and breathe.”

The MRI is also very nice. The nurses getting images of my heart look at me in a way that’s familiar. I am a small individual, and even though I’m currently 30, I still get clocked as 13-14 years old. I usually hold disdain for people that treat me like a child. But when I was getting my heart scanned, it was nice to have someone around treating me like a child. Like a school teacher, school nurse.

“You’re too young to be getting heart problems.”

She looked at me with concern, and then with steely resolve to make me as comfortable as possible in her care.

Meditation has not really ever suited me. Once, in college, I experienced a guided meditation. I was told to imagine scenes like escalators, and numbers, and to relax various muscles by name. I could feel my body tense, my jaw clench, my mind shake. When the lights came on, I felt my breaths become shallow, erratic, and tense.

I’ve never needed to squeeze the alert button when getting an MRI. Being forced to lie down, face inches from the interior of a giant imaging tube (whirring so loud they put headphones on you), creates a greater sense of calm in me than a guided meditation could. It is a guided meditation. I have to lie there, and I can’t move. I have to hold my breath for 15 seconds, and then breathe, and then hold.

“Breathe.”

Through my headphones, I get encouraging words, instructions, compliments.

I’m also alone, by myself, hugged by the machine, encased, swaddled.

“You’re doing great, a little longer this time.”

I don’t often feel like a collaborator with the medical staff around me, but when I get some kind of imaging I become a kind co-photographer. I move my hips, legs, torso.

Trust Me

Doctors sometimes feel they don’t need to earn your trust. I’m not sure how trusting I felt when I looked up from the floor at the nurse sitting next to my mother. I had just woken up after passing out from over-exertion on a treadmill. I had to trust my mother’s account of the event. As my mom explained, after running for a few minutes, I fell, passed out, threw up, and came to. The pediatric cancer center in Carmel Indiana had some insistent physical therapists.

Physical therapists don’t understand trust. They call for it, demand it. They take the body—the body in pain, the body in recovery—and twist it. I know that physical therapy is good, and that physical therapy before and after surgeries improves outcomes, reduces atrophy, builds strength and flexibility. It doesn’t make friends, though. A bad physical therapist doesn’t understand pain, doesn’t know pain. A bad physical therapist is a choreographer, is a stunt coordinator mapping your movements so that you can hit your mark. A bad physical therapist will never tell you that your body might never be the same, that you may always be in pain, you may never move like you did before. Doctors can’t do a factory reset. Trust me.

Cell phone use is not allowed

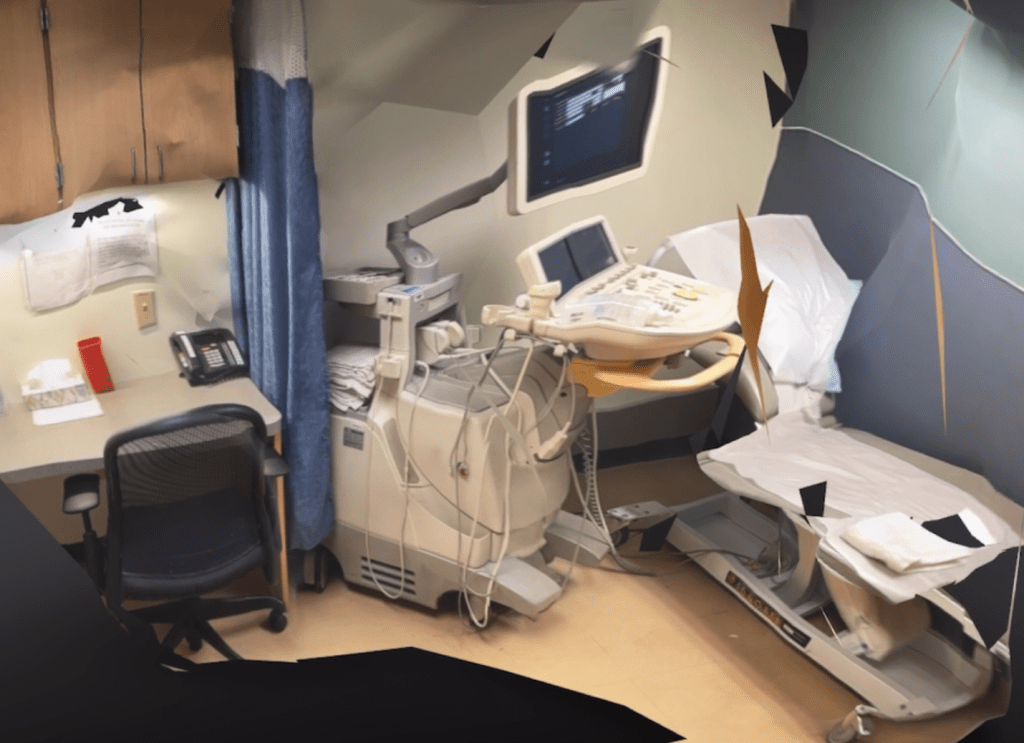

I started taking photos of every doctor’s office I go into. I’m not entirely sure why I do this. Partly, it’s because the “don’t use your cellphone” signs in the patient rooms are ridiculous. The rooms are mostly the same: converted office rooms garnished with linoleum floors and small sinks. There is usually a patient chair lovingly dressed with a crunchy paper roll.

At my current set of doctor’s offices, the computer in each room has the same screen saver with helpful tips for physicians (like how to prevent sepsis and reminders to make sure to ask for the both patient’s name and date of birth). The only things that distinguish these rooms from each other are the anatomical illustrations on the walls. As someone who visits doctors a lot, I appreciate the change in view.

Maybe I just like documenting these spaces because I want a record of how I spend a large portion of my time (proof that I wasn’t at Target all those days I had to take off work). Regardless, I take these photos and probably will continue.

Lie to your Doctors

I lie to my doctors and I think that probably other people do as well. Not when anything is particularly life-threatening, like when they ask, “how high was your home blood pressure?” or “are you experiencing any pain?” But I might lie when my doctor asks something, something else, something other than the thing they are asking, asking behind me, asking about me, asking for me, on behalf of me, supposedly, to get to the truth, the truth that is the health of me, if only I could get out of the way. I’m in the way.

Elaine Scarry, in her book The Body In Pain, describes how doctors, while in a position meant to speak for those in pain (“as many in the throngs of pain can’t speak for themselves in moments of pain”), commonly see themselves rather as detectives searching for truth beyond the patient, the “unreliable narrator” in the story of their own body. Scarry elaborates:

“…for the success of the physicians work will often depend on the acuity with which he or she can hear the fragmentary language of pain coax clarity and interpret it…many people’s experience of the medical community would bear out the opposite conclusion, the conclusion that physicians do trust (hence hear) the human voice, that they in effect perceive the voice of the patient as an unreliable narrator” of bodily events, a voice with must be bypassed as quickly as possible so that they can around it and behind it to the physical events themselves.”

Medical professionals ask questions like: “You sure?” “These results don’t make sense. Can you tell me why these numbers are this high?” Every symptom is a mystery, and they are Dr. House on the case, ‘cause they are the “best damn doctor we got.” When I get questions like these, I lie. I tell them anything. Cause I know the real answer, and they don’t want that answer. I’m ill. It’s an answer my doctors don’t want, because it might not be solvable, it might not be a problem, it might not be the right problem. Doctors lie too. They look at you, at your face, in your eyes, (or not at your face or in your eyes), at your chart, your blood work, your numbers. They’ve got your number.

They say, “that’s normal, don’t worry about that.” But you know it’s not normal. If it were normal, you would have experienced it before, when you were normal, normal-er. And you know you aren’t normal because you are seeing an onco-cardiologist, who is in contact with your PKD nephrologist, who saw that you visited the rheumatologist, and when you met with your oncologist, they didn’t refer you to an endocrinologist, because in her words, “you already have quite a few doctors.” When your doctors ration your referrals because they understand you are over-burdened with “care,” you know you are no longer normal. More importantly, I reserve the right to worry. Liar.

Lying to your doctor is a delicate thing. Surely it weakens the bonds between patient and doctor—the magical strings of light tied by a winged Hypocrites. That bond gets strained after describing your level of physical activity as “pretty good” instead of “work from home okay.” Sometimes, you will need to ask something that lives outside of your doctor’s knowledge, something your doctor doesn’t know. Sometimes your doctor will take this as a threat. Because they’ve trained for this! They’ve trained for years, sussing out silly non-cooperative patients, silly patients that don’t know any better, silly patients that do know better but don’t know best.

Then, you get more questions, or you get more tests (take home tests, home work, proof work, show your work, show your proof).

“I want you to bring in your blood pressure monitor.”

“Bring your blood sugar monitor.”

“I’m going to test it against ours.”

“I’m going to compare those to a blood test.”

“Let’s add a hemoglobin A1c test to your next labs.”

“Why don’t you take a 24 BP monitor.”

“I want you to track all of your food for the next week.”

Some tests are best done at home, because home is where normal happens. White coat syndrome—the name given to the condition of someone’s blood pressure being higher at the doctor’s office than at their home—is common. But home blood pressure readings are subject to patients, patients are subject to error, to failure, to tampering, to lying.

The only doctor I accused of lying to his face was a resident at the pediatric hospital I was in. I was in a tiny room for cancer patients (certainly not for bodies, as the room had no running toilet. Instead, a bed pan was lovingly placed in the shower.) A small window was in the upper right corner of the room, I corner I couldn’t reach. The location of the window mattered very little. It wasn’t much larger than a piece of paper—and it had metal bars installed in front of it. There was a small TV in the same corner of the room. A shit show. The resident treating me that day, (I do not remember his name as he took no time to remember mine), told me I should eat a diet of leafy greens. This is not unusual. Except I was on a strict diet—an immunocompromised diet, a decontaminated diet, an anti-fresh diet, a processed or expertly cleaned diet. The hospital opted for processed. This was one fact I was hyperaware of, as I had not eaten greens in months. Notorious for microscopic bacteria (that might normally be safe to eat), leafy greens were literally and metaphorically off the table.

The resident doctor, empowered, bolstered, and emboldened by his status, his student debt, his title (he was a resident and he resided here, this was his house), directed me to eat this green meal. I was like Daniel of old, who, when offered meat from the Babylonian king, ate only the pulse and wine and was not sick. I abstained from the devil’s salad. I rebuked this leafy fiend, this food felon. I scorned this man, this child. His supervising doctor shook his head at him and regretfully confirmed the truth, a truth—my truth. The doctor to be, the doctor in training, the doctor in training wheels, the big-wheel doctor left in shame with his tail between his legs. I knew the truth, because I honestly would have loved a salad.

Lying is a defense mechanism. Like flinching, or screaming. A question out of the blue, out of the sky, out of an ass, out of hot air, a question that comes at you that throws you and you have to flinch. “Umm, nothing happened.” “Yeah I’ve eaten perfectly this month,” Because the honest answer is more like: “I couldn’t afford all of these different treatments, so I stopped taking one medication (against your recommendation) because talking to you about my material conditions is truly more painful.” Or “I ate quite well this month, though I did eat out, I ordered out, I ordered in. I ate frequently, infrequently. What did you eat? What do you want me to eat? Will you cook for me? Will you buy my groceries?” Doctors are lying because they aren’t asking you what you ate; they are asking why you ate what you ate, because they know you ate what you ate because they know, because they are doctors and doctors know and patients do not because patients are liars.

Sources

Scarry, Elaine. In The Body in Pain, 18–19. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. 19 20